Muuratsalo Experimental House, Alvar Aalto

Gothenburg City Hall, Erik Gunnar Asplund

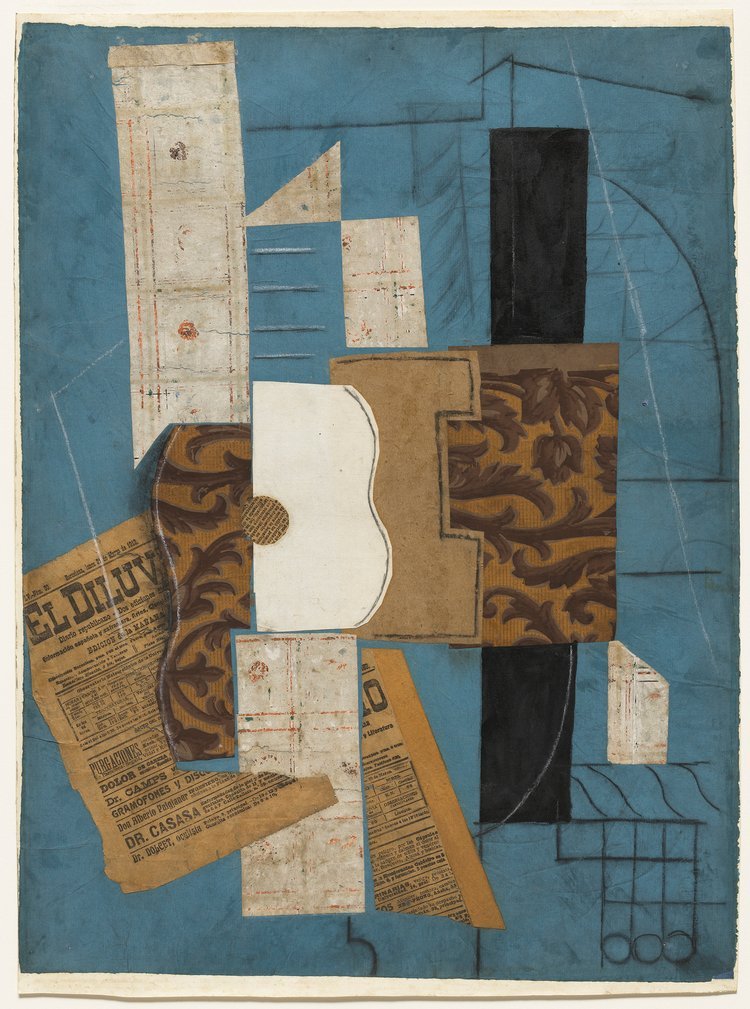

Pablo Picasso, Guitar, 1913

….a reference to the real nature of things, a step from illusion to reality (or its imitation?) was made……..overlapping fragmentary forms placed, juxtaposed, layered in conversation with one another……………While the emergence of collage is frequently placed in the twentieth century when it was a favored medium of modern artists, its earliest beginnings are tied to the invention of paper in China around 200 BCE. Subsequent forms occurred in twelfth-century Japan with illuminated manuscripts that combined calligraphic poetry with torn colored papers. In early modern Europe, collage was used to document and organize herbaria, plant specimens, and other systems of knowledge……….the work of artists as invention by gathering, or, collatio; a practice of picking, choosing, and placing predates the accepted derivation of collage from the French verb, coller (to glue), by several centuries……….Collage and assemblage are art techniques involving the creation of artworks by combining found or pre-fabricated elements to form a new composition………..Montage implies another kind of formulation of visual criteria. It is more closely aligned to the theory of images, it tends to the cinema, it tends to slicing and rearranging elements outside the picture plane……….Assemblage can mediate between collage and montage………..

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/ey-exhibition-rodin

Rodin’s innovativeness resided in the fact that casting versions became a systematic part of his creative process…..…..Rodin also took advantage of the opportunities that multiplication afforded within a work, using the same figure in different positions: the inspiration for Three Faunesses (before 1896) was thus drawn from a figure Rodin employed four times on The Gates of Hell. Likewise, the male figures in The Three Shades (before 1886) were borrowed from Adam (1880-81, itself inspired by the pose of Michelangelo’s Slaves)……………In the late 1880s, in the period of intense activity revolving around The Gates of Hell, Rodin built up a large stock of models of complete figures and fragments, which he could delve into whenever he wanted to experiment with assemblages and transformations. In the early 1890s, Rodin continued his investigations into partial figures (commenced with the Torso of the Walking Man in 1878). He dismantled and reassembled existing sculptures in endless combinations. By casting different parts of figures separately, he could rework the overall composition of a piece, without having to rework everything. Rodin joined his sculptural studies, or bozzetti (c.1890-1900), onto other figures through a process he called marcottage, generally leaving the joins visible in the finished sculpture, thus reviving the idea of non finito borrowed from Michelangelo……….While Rodin drew his inspiration from ancient statuary and Michelangelo’s works, especially fragmentary figures, his own works should be discussed more in terms of partial figures. A fragmentary figure is initially executed as a whole figure, which is subsequently damaged. In a partial figure, only the elements that are visible were actually executed, as was true of Rodin’s works, even if most of his partial figures made after 1890 were casts and enlargements of earlier works. By enlarging fragments of figures, instead of whole figures, Rodin abandoned the practice of representing the body in its entirety, thereby freeing himself from Phidias and Michelangelo’s artistic canons and problematic issues of anatomical proportions. Flawless in form, the fragment thus earned its independence, broke away from the figure to which it had originally belonged, and became a work of art in its own right.

THE WHOLE IS THE UNTRUE: ON THE NECESSITY OF THE FRAGMENT. Almost everything we know about the past comes from physical and narrative fragments. Yet a fragment is not simply the static part of a once-whole thing. It is itself something in motion over time, manifesting successively or variously as object, evidence, concept, and condition. The pieces gathered in this volume—written by scholars of art, art history, archaeology, literature, philosophy, psychology, numismatics, and film—investigate the significance of the fragment, whether received or created. Each essay offers a meditation on a distinctive moment in the history of the fragment, ranging from spolia in late antique architecture to the practice of collage in the modern period.

Fragmentary Forms: A New History of Collage, asks what happens when we try and trace a history of collage back across time and space. Moving beyond narratives of modernist invention, the book is concerned with moments of invention, exchange and expression on both intimate and global scales. Some of the larger histories told on its pages are those of technological revolution—the advent of mass production, for example, which transformed our engagements with, and understandings of, the material world.