ARCHITECTURE — A SYNOPTIC VISION: EXAMPLE OF AN EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY

TURTLES DO NOT SUCCESSFULLY MATE WITH GIRAFFES: PLURALISM VERSUS CLOUD

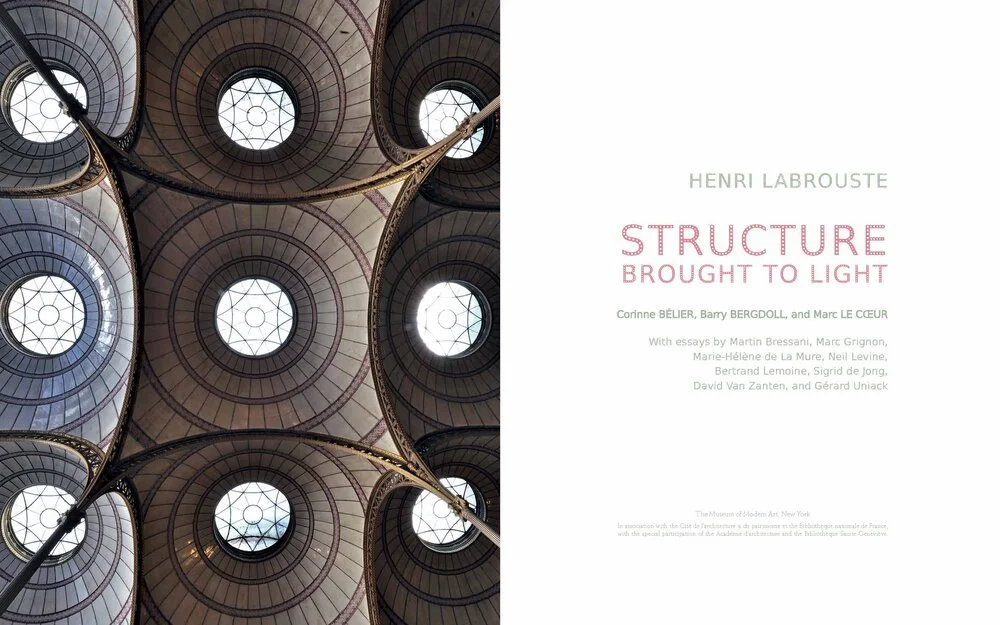

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light is divided into three sections: The Romantic Imagination; Spaces of Knowledge; and Prosperity and Affinities. The exhibition’s first section covers the period from 1818, the start of Labrouste’s artistic training, to 1838, tracing the development of Labrouste’s philosophy of architecture and practice in two settings—ancient Rome and modernizing Paris—which Labrouste conceived of as architectural laboratories. During the five years Labrouste spent at the French Academy in Rome, he began to explore a notion of architecture as the product of layers of history, societies in evolution, and of historical change, and he proposed a new approach to architecture’s capacity to carry social meaning.

Relative & Evolutionary: Henri Labrouste and the Romantic Lessons of the Past——-Nov 15, 2021

Henri Labrouste is the best known of a generation of architects in France who placed the understanding of history as a dynamic process at the heart of debates over rules, standards, and style in architectural practice.

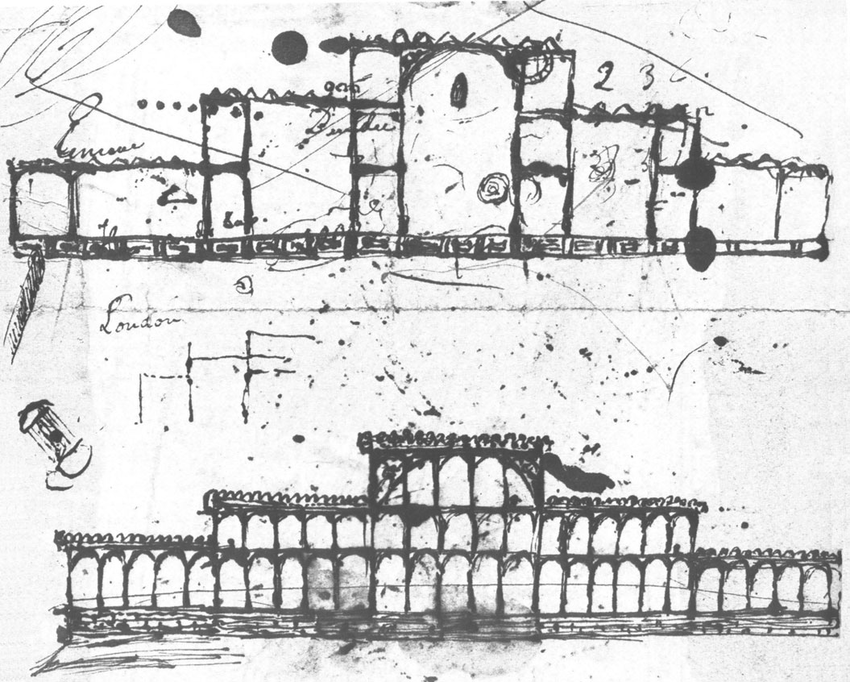

In 1828, the year the term avant-garde entered vocabularies as an artistic stance rather than a military practice, Labrouste rocked the French Academy of Fine Arts by proposing a new understanding of classical architecture and its relationship to the present — and to the very idea of rules, as well as the notion of imitation vs. invention.

In his two most famous designs, the Bibliotheque Ste. Genevieve and the Bibliotheque Imperiale (today Nationale), he offered at once a synthetic view of historical sources for architectural design and a radical new way of incorporating the materials — iron and ceramics — of the industrial age.

By the time the Bibliotheque Ste. Genevieve was nearing its completion, Labrouste's close friend Louis Duc offered a prize for architectural innovation. French classicism had been placed on a bold new trajectory.

A Lecture by Barry Bergdoll

From the Soane Lecture Series 2021-2022: Rule and Invention

Hosted by Sir John Soane's Museum Foundation

The Crystal Palace and its Place in Structural History

Completed in 1851 to house the Exhibition of All Nations in London, the Crystal Palace was the first large public building that departed completely from traditional construction materials and methods. It was the first major building to be conceived by its design engineers, William Barlow and Charles Fox, as a rigid-jointed iron frame and one of the earliest to use horizontal and vertical cross-bracing to carry wind loads. Working closely with the contractor John Henderson, the designers also applied their knowledge of modern production engineering methods to ensure the building was constructed in the incredibly short time of 190 days. Within twenty years the iron frame, supporting thin walls of masonry, would become established as a viable alternative to load-bearing masonry walls for large buildings.

otto-wagner. Realized in two phases, the first in 1904 - 1906 and the second in 1910 - 1912, the Postal Savings Bank was Otto Wagner’s first major building commission. Wagner’s approach to design was closely tied to that of the Secession—a progressive group of Austrian artists, architects and designers who pursued artistic rejuvenation in combining quality building processes with new materials and technologies, and expressive modernist forms. Secessionist architects, including Josef Hoffmann and Joseph Maria Olbrich, were drawn to the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk—or the “total work of art”—in which all aesthetic elements are subordinated to the whole effect. In practice, this concept promoted artistic craftsmanship across a wide spectrum of disciplines and favored collaborative models of creation over individual authorship.

Louis Sullivan: The Struggle for American Architecture. This tribute to architect Louis Sullivan tells a sweeping story with a wealth of visual detail. The rise and fall of Sullivan’s career originates with the 1871 Chicago fire, which made the city a blank slate for ambitious architects. In the late 1800s, Sullivan, who had made his way west after a rigorous École des Beaux-Arts education, created an authentically American architecture at a time when most buildings aspired only to knock off European styles. His commitment to originality led him first to the pinnacle of success with notable early skyscrapers and later to a swift decline due to changing customer tastes and an economic depression.

In his book Contemporary Curtain Wall Architecture, Scott Murray traces the evolution of the curtain wall, from early skeleton-frame structures of the past to today’s complex and technologically advanced configurations. Presenting twenty-four detailed case studies of exemplary structures completed in the twenty-first century, he reveals the curtain wall as one of the most enduring and malleable concepts of contemporary architecture, capable of adapting intelligently to site constraints, utilizing resources efficiently, and offering unprecedented opportunities for innovations in digital design and fabrication, material detailing, and aesthetic expression.