FG: I absolutely don’t think being a purist is any more true to the nature of architecture.

You’re right that some critics look at my buildings and complain that the interior walls don’t correspond to the exterior walls. But making a building where the two are perfectly lined up isn’t any simpler or any more honest. Let’s take the example of a small wood house, like they used to build in the ’50s. You see one of these under construction, with all the wood studs framed up, and it’s so beautiful you could die—just a simple timber frame, totally pure, right? I used to see thousands of those tract houses being built when I was driving around Southern California. I loved looking at them.

But then what happens? You bring in the plumbers, you bring in the electricians, you bring in the HVAC contractor, and everybody starts drilling holes in the studs and moving things around and then taping it all back together. They totally violate the structure—they torture the purity out of that thing. So, there’s a conflict between this idea of an ideal structure and all the things you need to put into a building to make it a building.

JR: So you’re saying that the appearance of honesty is itself a kind of fabrication?

FG: Absolutely. And when you try to make a building with a tight skin stretched over the structure, it costs a fortune. Go to Mies van der Rohe’s pavilion in Barcelona and look at the columns intersecting with the roof slab. It’s so beautiful, this thin column hitting a roof that’s just six or eight inches thick. But then you look at the drawings and you realize that it’s not even a structural connection, it’s just two things touching! And you start to understand all the structural gymnastics Mies had to go through to make that building look honest.

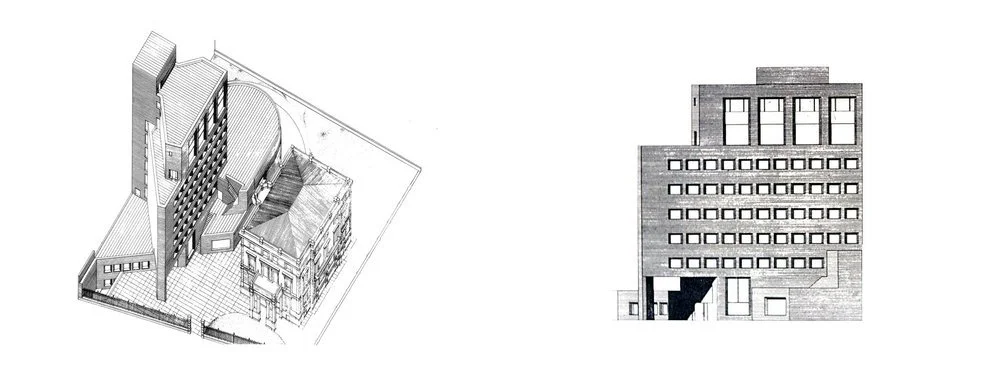

That’s why I have always said we should separate the mechanical elements of the building from elements that provide shelter. And if you have a cavity between the exterior and the interior where mechanical systems can go, then they can also be changed without completely taking apart the building, and if you’re making architecture in the twenty-first century, that seems like a good idea. So we can argue forever about the inner skin and the outer skin and how far apart they should be and how much they can deviate from each other, but at the end of the day the space in between isn’t wasted.

NONFINITO – THE ART OF UNFINISHED……….Incompletion admits to being part of a process. In its very failure to perfect the image, it lets us to see how the image has been constructed. The archeology of that image is revealed, how it came about. With the twentieth century’s emphasis on the materiality of the medium, it is clear that for many modern artists engagement with a process is more important that the completion of some pre-ordained blue-print. Jackson Pollock would work on a drip painting until it was time to abandon it. There was nothing to perfect except the process……….